All posts by user

The hidden life of the Arctic

Clive Tesar visited the sea ice edge near Pond Inlet, Nunavut, to capture images and videos of the diverse life on the fringe of the Last Ice Area.

The massive bulk of the bowhead whale floats in a crack in the ice, barely more than an arm’s length away. It lets out a long lingering breath, then slips away to its life beneath the ice. I’m left on the floe edge, where the ice meets the sea. I’m standing on metre-thick sea ice, about ten kilometres beyond the tip of Baffin Island in Canada’s Arctic. Once the whale has slipped away, the scenery looks like the Arctic pictured so often, a vast white waste, devoid of life. But moments such as this remind you that the life is there, all around you, if you look for it.

Sometimes it teems at the floe edge, the most productive part of the marine environment, thanks to nutrients melting out of the ice. Moments after the whale submerged, some thick-billed murres popped up from under the ice, looking vaguely affronted as they realized they had company, and scooted off across the water, murmuring to themselves. Another few minutes wait brought a pod of narwhals, their gentle sighs announcing their presence before their mottled backs were visible among the pack ice. We dangled an underwater microphone, and heard the eerie descant whistle of the bearded seal.

Walking across the land, the purple saxifrage was in flower in patches not covered by snow. An arctic hare fed amongst the flowers, apparently oblivious to the fact that his white fur afforded him scant camouflage on the greening tundra. Lemmings scampered off at our approach in a small river valley, though they should have been more concerned about the gyrfalcons nesting in a cleft in the cliffs above.

The arctic hare populations in the Arctic experience large swings from population boom to bust, and numbers of hare predators follow similar cycles. Photo: Clive Tesar / WWF

Further up the valley, piles of rocks encrusted with sod – these were the homes of Inuit for thousands of years, as they harvested the bounty of the floe edge. Bowhead skulls integrated into the structure of one sod house made a tangible symbol of the success of their continued relationship with the land and sea here.

I’m here to bring the life of the Arctic back with me, in photos, videos and stories, to help people worldwide appreciate that the Arctic is not an empty wasteland, but a place where life exists in cracks in the ice, in folds of tundra, in crevices in cliffs, and in the communities that grew up around the places where life was most abundant.

June 2014: Bowheads and breaking ice

Arctic whale specialist Pete Ewins gives us an update on the bowhead whales being tracked by Nunavut Wildlife Management Board and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada.

As southern Canada starts switching on the air conditioning units and breaking out the fans in late June, the Arctic sea-ice is still there according to the satellite snapshots. But such technology can now tell us even the depth of the sea-ice – and that is what counts at least as much as the area of ocean with ice cover, at least from the point of view of marine wildlife like the ice-evolved bowhead whale! Especially towards the southern edges of the ‘Arctic’ sea-ice thickness has been dropping dramatically in the past decade – meaning that it melts earlier each spring, which increases the length of the open-water summer period.

The amazing compact technology now packed into a mobile-phone sized transmitter unit, and attached to the 100-tonne bowhead whales, has in recent years been able to give conservation science and decision-makers alike invaluable facts about where the whales spend their time, and hence help identify and protect these most special areas.

The stunning news this month is that bowhead whale 114495 (currently off Southeast Baffin Island in areas of ever-opening summer Arctic ocean) has had its radio transmitter device on for 2 years now – and its still transmitting vital information back to the scientists via orbiting satellites.

WWF is excited to be able to help share these spatial data. These whales move a lot, but they home-in on a relatively small number of very special areas for doing key things like raising their dependent young, feeding, and resting safely well out of reach from their main predator – killer whales.

Knowing where these key areas are for bowheads and other magnificent Arctic wildlife still in their natural habitats is crucial as our society plans for future increased human activities like commercial shipping, oil-gas exploration, and large-scale mining and ore shipment, and commercial fishing.

Not able to edit a page?

In case you are having trouble editing one of your pages (the icons are greyed out?), this is because we made a small adjustment in the CMS permission profiles. Continue reading

Putting a price on Arctic biodiversity

Berta Tokeinna and son Jeffrey pick berries on the tundra, Serpentine river delta, Alaska, United States

© Global Warming Images / WWF-Canon

Those of us who have experienced encounters with some of the fascinating animals of the Arctic – narwhal, polar bear, ivory gull or some other Northern species – will not easily forget that moment. Or perhaps you have enjoyed a fine meal of reindeer, caribou, or whitefish. In that case, Mark Marissink says you have partaken of some of the many ecosystem services that Arctic biodiversity provides. But do we need to put a dollar value on the fruits of biodiversity, to protect it? Mark is with the Nature And Biodiversity Research and Assessment unit, under the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Let us know what you value about the Arctic by July 15, 2014.

Nature, biodiversity, has a value. It has a value because we can enjoy a walk in the forest or the view of a birds’ cliff or just by being there. Indeed this value has been recognized by almost every country in the world, as witnessed by the very first lines of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity which state we are “Conscious of the intrinsic value of biological diversity and of the ecological, genetic, social, economic, scientific, educational, cultural, recreational and aesthetic values of biological diversity and its components”.

But in day-to-day decision making, nature is still often seen as a special interest for a few people who like rare species, rather than something that is of importance to all of us. This is where the concept of ecosystem services comes into play. Ecosystem services are the benefits that people receive from nature. Some of those benefits, such as food, firewood and timber, are obvious and are also regularly traded in markets. Others, such as flood control through forests or wetlands, or pollination of orchards by insects, can be less visible and are often taken for granted. That means they are usually overlooked when decisions are made that have an impact on nature, and we may suddenly find ourselves without the flood control we have always relied upon.

Ecosystem services are often divided into four categories:

- Supporting services are the basis for our survival on earth. They include photosynthesis, soil formation, nitrogen cycling, and they lay the foundation for the other ecosystem services.

- Regulating services can be the pollination and flood control of the previous example, but also local and global climate regulation by vegetation.

- Provisioning services provide us with products from nature for use as food, building materials, and fuel.

- Cultural services constitute a diverse category that includes our enjoyment of nature, inspiration or the benefits to our health.

By looking at nature through the concept of ecosystem services, the idea is that it will be easier to convince those who do not believe that they are interested in nature that nature should be of interest to them. In order to make this even clearer, it could be useful to actually put a value to those ecosystem services. In that case, benefits of a decision, for instance to build a new road, could be compared to its costs to ecosystem services. In some cases, it is not too difficult to valuate changes in ecosystem services; sometimes this can even be done in direct monetary terms, for instance changes in timber production when trees have to be cut to build a road. More often, however, it is much more difficult and in many cases we will have to be content just to know that these values exist, without exactly knowing how large they are.

Many people object to the concept of ecosystem services, and especially to the idea of putting a value (“a price”) on nature. They see it as too human-centred or disrespectful of nature’s own value. Traditional knowledge often takes a completely different view of life, and also many environmentalists think it is inappropriate to disregard the intrinsic value of nature in this way. Others see ecosystem services as the only way to make nature count in decision making.

To date, the concept of ecosystem services has been studied to a limited extent in the Arctic, especially when compared with other regions of the earth. Studies of supporting and regulating services are largely absent. Providing and cultural services have been studied in more depth, and the chapter on ecosystem services in the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment describes examples of four provisioning services – reindeer herding; commercial fisheries; commercial and subsistence hunting, gathering and small-scale fishing; and recreational and sport hunting – and two cultural services – tourism and non-market values. Since so much of the work on ecosystem services has been done in very different environments, ongoing studies, led by WWF, on how and where an assessment of the ecosystem services provided by Arctic biodiversity can take place will be of great importance.

How do you put a value on Arctic biodiversity? Let us know what you value with this survey by July 15, 2014.

This article was originally featured in The Circle 02.14.

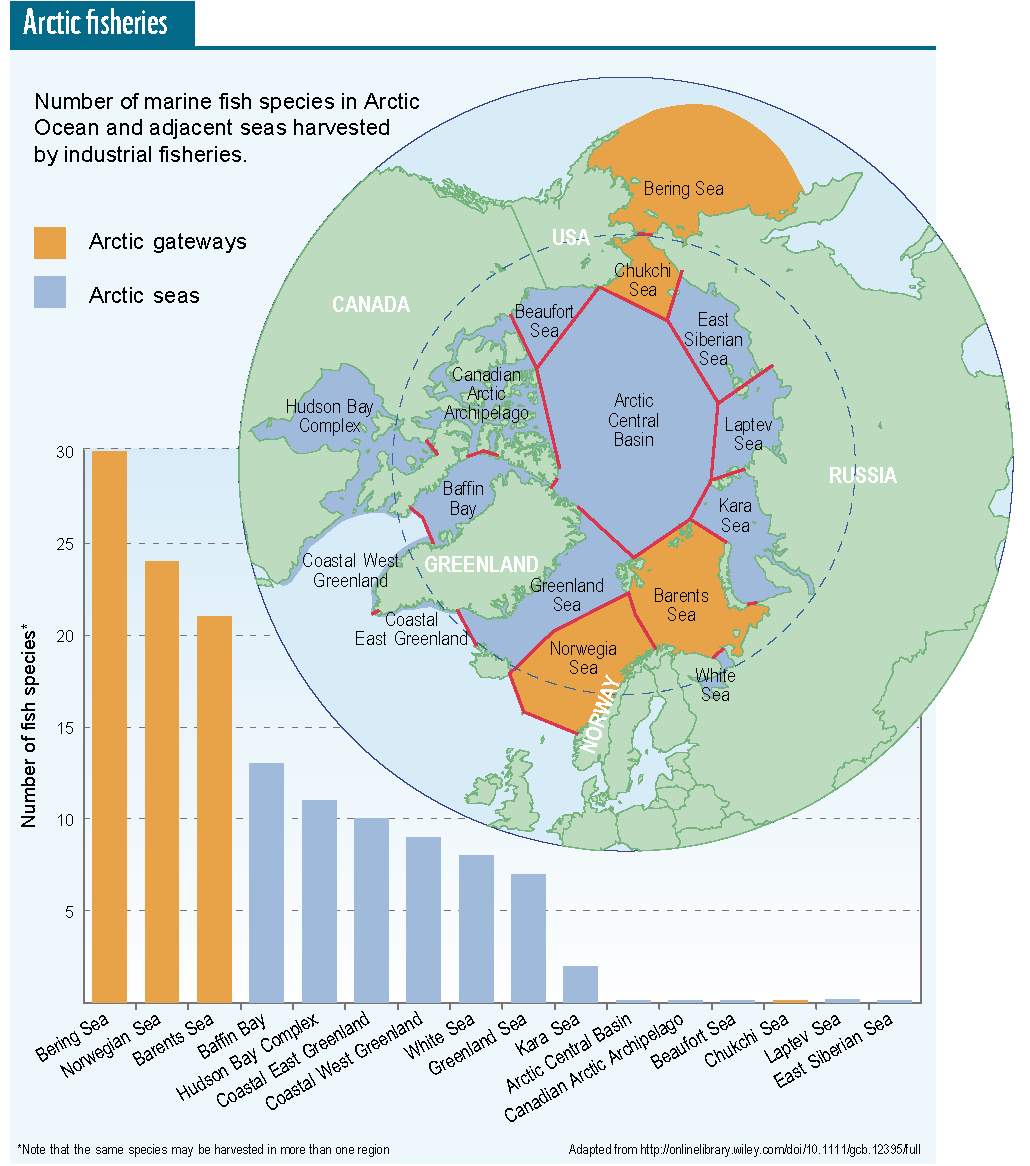

Fishing for the unknown

This article originally appeared in The Circle 02.14.

The Arctic seas are under tremendous pressure from climate change and expanding human activity of unprecedented scale. JØRGEN SCHOU CHRISTIANSEN says our biological understanding of Arctic marine fishes is virtually absent, and strict precautionary actions are imperative. Christiansen is a professor of fish ecology at the Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway, and guest professor at Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland.

THE NEWLY RELEASED report on Arctic biodiversity presents the first comprehensive assessment of about 635 marine fish species across the Arctic Ocean and adjacent seas (AOAS). The most important outcome of this exercise is that we have finally structured our ignorance and identified some of our knowledge gaps. In short, our biological understanding of Arctic marine fishes is practically absent. Scientific uncertainty is difficult to broadcast and hard to sell, but it is nonetheless essential as it calls for strict precautionary approaches towards Arctic resources.

A few years ago, headlines in the media gave the misleading impression of Arctic fishes being overexploited. Subsistence fisheries along the Arctic coasts have been going on for centuries and the reconstructed catch records for a range of fishes such as whitefishes (Coregonidae) and salmonids (Salmonidae) accumulated to about 950 thousand tonnes in 57 years (1950-2006). This is absolutely minuscule compared with, for example, annual landings of more than 1 million tonnes from a single stock of herring (Clupea harengus) in the Northeast Atlantic. What is most disturbing, though, is the emerging full scale exploitation of petroleum and living resources in hitherto pristine parts of the Arctic seas.

Among the 635 AOAS fishes, only 60 (fewer than 10%) are classified as being true Arctic. The remaining fishes belong to sub-arctic and southerly seas. The widely used phrase “Arctic fisheries” is false from a biological standpoint. Within the AOAS, industrial fisheries target about 60 species of which only three (5%) are Arctic: the codfishes polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and navaga (Eleginus nawaga), and the Arctic flounder (Liopsetta glacialis).

Databases covering the Arctic Ocean and adjacent seas hold a wealth of valuable information for the commercial species. But it is also a fact that data on non-target fishes are notoriously poor – bycatch species are either misidentified or lumped into categories of little biological meaning. This is particularly true for cartilaginous fishes such as sharks and skates, and species-rich fish families such as sculpins (Cottidae), snailfishes (Liparidae) and eelpouts (Zoarcidae). So, to keep up a precautionary view: better to be data deficient (“we haven’t got a clue!”) than misinformed (“our databases may show…”).

In light of ocean warming, targeted fishes spread rapidly into yet unfished parts of the arctic seas and marine toppredators, in the shape of industrial fishing fleets, obviously follow. For example, Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) is now common on the arctic shelves around Svalbard archipelago at latitude 80°N. Bottom trawls are by far the most used and most destructive gear in groundfish fisheries. The vast majority of Arctic fishes live at or near the bottom and do not migrate. Therefore, they are particularly vulnerable to conventional bottom trawling as they are lost to bycatch and destroyed seabeds. Although of no direct commercial value, bycatch species make arctic ecosystems work by feeding seabirds and marine mammals – wildlife that forms the livelihood of Arctic peoples. In contrast to the Southern Ocean, the Arctic is neither an outpost nor a frontier but homeland to Arctic peoples. They are the first to feel the pressures of climate change, big business and reckless actions from some environmental activists.

The detection of valid species and how they work in context of ecosystems is at the heart of biodiversity assessments based on scientific credibility and legitimate conservation and management actions based on societal values. Several Arctic fishes are controversial and difficult to identify and basic questions remain unanswered: how do fishes interact as prey and predator; how do they grow and reproduce; how old do they get and how do they cope with heat and pollutants?

We clearly need to integrate traditional/ community knowledge held by Arctic peoples and the natural sciences for legitimate conservation and management actions. This is indeed a huge, but not unsolvable, task. It must be based on mutual respect for the perception and rights of Arctic peoples to wildlife and habitat, and the methodological needs and rigor of science. Traditional ecological knowledge may provide valuable information to science on species distribution and abundance, shifts in biological events and changes in species occurrences and habitats. On the other hand, science may give useful advice on pollutant loads in wildlife and forecast potential consequences of climate change. Science needs traditional knowledge and traditional knowledge needs science. In the end, we all fall victim to failed conservation and management policies.

Read more on this in a recent Open Access paper in Global Change Biology.

Server maintenance May 19th

We are currently rolling out security patches on all of our servers. The next maintenance will be done on May 19th 2014 at 09:30 am GMT on the peggy and wwf-web-1 servers. Continue reading

Server Maintenance May 12th

This is happening today! Continue reading

New CMS Dashboard

We hope you like the new CMS Dashboard 🙂

Some more new features will be added soon. Send us your feedback to support@wwfinternational.zendesk.com

thanks!

WWF Tech & Apps

Server Maintenance on May 12th (wwf-web-2)

There will be a security patch rolled out on all of our servers. The first maintenance will be done on May 12th 2014 at 09:30 am GMT on the wwf-web-2 server. Continue reading